While reading Disrupted, by Dan Lyons, something started to jar on the eye – apart from the weirdly specific Scientology jokes, which were explained when, in the latter pages of the book, he mentioned reading Lawrence Wright’s Going Clear during the period covered by the book. Specifically, I kept running into what I’ll call “the apposite of an allusion” (Roll credits…), i.e., an allusion that is immediately followed by a capsule summary of whatever was being alluded to.

E.g., “I feel like Dorothy.” becomes, “I feel like Dorothy, the little girl in The Wizard of Oz who is transported to a strange land called Oz.”

Going through the book after I’d finished it, I pulled out all the passages that seemed relevant to my little five-minute-wordplay of a title (all page numbers refer to the hardcover edition).

feeling like the character played by Bill Murray in Groundhog Day. (p. 23)

Most of the allusions or other references are to movies, which brings up the question of whether to reference the character or the actor who portrayed them. In this case, it’s pretty clear cut – I’d wager most people (myself included, viva Wikipedia) have no idea that Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day was named Phil Connors, certainly not a good enough idea so as to let them read on uninterrupted. They’re not fluent in Phil Connors. (So – especially given the quote about Donnie Brasco later on, from p. 199, this feels like it should totally have just been “feeling like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day.”)

If the boss wants us to waste half a day on Romper Room bullshit, we could at least have some fun. (p. 60)

Solid enough, nothing that would make one stop and blink as they were reading. (Though part of that’s the title – even if you didn’t know the show itself, the youthful connotations of ‘romper’ and the alliteration in the title are a good hint it ain’t Masterpiece Theater.) Which, reading the book as a whole, leads to an odd sense of cognitive dissonance regarding the audience – going by what allusions are or are not glossed in some way, Lyons assumes an audience familiar with, in addition to the aforementioned Romper Room:

- Groundhog Day

- Glengarry Glen Ross

- Argentinian Dirty War

- Showgirls

- Battlefield Earth

- The dramatic stylings of Late-Period Nicholas Cage

- Tony Robbins

But which is not down with, up on, keyed into (to varying degrees):

- Up

- Office Space

- MIT’s Sloan Business School

- Will Ferrell, specifically Old School and Zoolander

- Back to the Future

- Logan’s Run

- American Psycho

- Being There

Some of these make sense – for me, at least, Being There is something I’ve glanced at the Wikipedia for once or twice, and it would have taken me a cycle to recall the relevance of age for Logan’s Run, but others are… not just puzzling from a pure audience point of view (who would pick up a book about working in a tech startup, with a picture of a person at a laptop in a unicorn mask on the cover, who doesn’t know of Office Space?) but also in terms of internal consistency. Someone familiar with Nicholas “NOT THE BEES!!!” Cage, but not Will Ferrell?

(And, incidentally, Will Ferrell and Office Space are disproportionately referenced throughout, because 1) Will Farrell is a significant element in a core anecdote, and 2) this book is basically trying to be (well, trying to fill the satiric role of) Office Space for the start-up scene. Oh yeah and also 3) Lyons was a writer for Silicon Valley, which was sort of literally “Office Space the series, but for the current start-up boom”, created by… Mike Judge. (And if you don’t know who Mike Judge is, that’s explained in one of the allusions referenced below!))

Imagine Glengarry Glen Ross, but instead of four sales guys there are a hundred, and they are all in their early twenties, all talking at once, all saying the same things, over and over again. (p. 97)

“… all that stuff goes out the window, and they bring in Alec Baldwin to give his steak knives speech,” (p. 98)

This sort of just works. So long as you know what’s being referenced. Without it, you can kinda get it, you know? In the first quote, you know that you’ve got a bunch of guys, making sales calls; and in the second quote, you can suss out that when times get tough, things get real cut-throat, real quickly. So it still sort of works (it doesn’t not work), but if you know the single most famous scene from Glengarry Glen Ross? You know exactly what’s being described.

It’s like living in Argentina during the 1970s. (p. 167)

– in the sense that, yeah, people are vanishing overnight, by lunch, without warning or due process or any semblance of humanity, but… It’s kind of weird compared to all of the other pop-culture allusions and, really, if you’re familiar with the Argentinian Dirty War, then this becomes in rather poor taste, or could be. Thus, its use presupposes a strongly shared cultural vocabulary, where certain things have become so familiar, lexicalized to the point of shedding their connotations, i.e. you can refer to Dirty War style disappearances without making people think of, you know, death squads.

This is still a good use of allusion, assuming a cosmopolitan, journalistic sense of cynicism and detachment to give a wink-wink, nudge-nudge tilt of the head towards black humor.

But it’s addressed to the same audience that is unfamiliar with Office Space and Will Ferrell, and that’s what makes it… weird.

I feel like I’ve fallen into a scene from Office Space. (p. 228)

This adds to the overall feeling of dissonance. While recognizing that, yeah, it can get hella awkward to have to keep glossing a specific movie reference, it’s also re-e-eally unlikely that anyone who didn’t know about Office Space on page 60 would have gone and seen it by page 228.

a look that a friend of mine calls “New England college girl going on a date,” meaning jeans, boots, sweaters. (p. 3)

Adds an air of youthfulness, adds just enough explanation that an isolated / personal culture’s allusion is made accessible at large, both parts contribute – this works.

the way I love movies like Showgirls and Battlefield Earth and anything with Nicholas Cage – movies that are so bad you can’t believe they exist, yet you’re glad they do, movies that are so bad that they’re good. (p. 48)

Where there are multiple possible interpretations, a brief gloss doesn’t detract much. Even though most readers would know what’s coming, there’s the possibility that he means, for example, “check your brain at the door” movies, instead of this. On top of that, it’s followed up with the personal reasons alluded to with the explicit “I” subject, as opposed to (if this were handled like the first mention of Office Space below) something like: “Showgirls, about a stripper’s journey to headlining a Vegas musical, and Battlefield Earth, the John Travolta vehicle based on a tome of Scientology space opera, and anything with Nicholas Cage, an actor whose recent roles have…”

That is, even if it’s pretty obvious it’s gonna be a “so bad it’s good” line, the elaboration elaborates on the meaning of the allusion rather than its object(s), and isn’t half bad.

who is a bit like Tom Bergeron, host of Hollywood Squares, America’s Funniest Home Videos, and Dancing with the Stars, only cheesier (p. 62)

I’d call this one more of an incidental allusion, in that the main thrust of the description is the cheesiness embodied in the host of the C-list shows listed – the fact that the same guy hosts all three of them (apparently? My life is better off that I don’t know this and don’t care to check) is a nice thread to string ’em on.

compares Zack to Dug, the peppy dog in the movie Up, who is constantly being distracted by squirrels. (p. 70)

Here… it’s borderline, and it may just be for me, because I haven’t watched Pixar movies that much, but this doesn’t strike me as obnoxious since Dug is a) not an ‘A-list’ reference the same way Office Space is, and b) while totally in keeping with Dug’s overall ‘Dug-ness’, the squirrel thing isn’t the only, or even primary thing you think of. (You are my prisoner, bird!)

That said, “peppy dog”… Thin ice, Lyons.

the crazy bald senior citizen from the Six Flags commercials, the one who wears a tuxedo and giant eyeglasses and dances around like a halfwit. (p. 151)

This, too, works, because this is basically the only way people refer to him (other than “that dude from the Six Flags commercials who looks just like Uncle Junior from The Sopranos but isn’t Uncle Junior from The Sopranos“).

The scene feels like something out of Office Space, the Mike Judge movie about life as a corporate drone at a company called Initech. (p. 60)

Here is where I first laid the book down, looked up and out into space, and wondered… what? First, unlike the example later where it occurs in spoken dialogue, repeating the same concept, just in different language or at more depth, is less welcome in writing. And here, it doesn’t even explain anything – if you don’t know what Office Space is, or if you know of it but aren’t with it enough to get the reference, then informing you that it’s a “Mike Judge movie about life as a corporate drone at a company called Initech” provides you with zero (0) additional utility as to figuring out what’s being described.

Unless, I suppose, you’re intimately familiar with the comedic stylings of Mike Judge, but also have never heard of Office Space. But that begs the question of, does such a person actually exist, other than – maybe – Mike Judge’s great-grandmother?

This reads like – and this sounds a bit harsh, but looking over all the examples I pulled out, I think that it’s less representative of the whole than I first thought – it was originally written as “The scene feels like something out of Office Space.” before some editor – either in Lyons’s head or a separate person – questioned the reference, or posited an imaginary reader that might question the reference, leading to the clunky apposite being tacked on.

Basically this is a version of Milton, the character in Office Space who loves his red Swingline stapler. (p. 61)

The character being described here isn’t really that much like Milton – his defining feature is malicious compliance, whereas Milton… just really, really likes his stapler. But Office Space gotta Office Space.

and has an MBA from Sloan (that’s the MIT business school) (p. 63)

I think what’s going on here is an attempt to capture a person’s breezy, insidery attitude – the person here would absolutely say that they have “an MBA from Sloan” because if whomever they’re talking to knows what that is, they know how great the person is, and if they don’t, well… sniff… there’s us and there’s them, dahling. (*cough* pleb *cough*).

Unfortunately, since it’s delivered from Lyons’s point of view, it ends up falling a bit disjointed compared to, say “finds a way to mention, within five minutes of meeting you, their MBA from Sloan. (That’s the MIT business school, they’d add if you looked puzzled or insufficiently impressed.)”

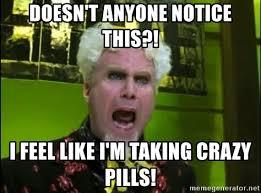

I feel like Mugatu, Will Ferrell’s character in the movie Zoolander, when he finally loses his patience and screams out: “Doesn’t anyone notice this? I feel like I’m taking crazy pills!” (p. 66)

I tried to figure out what this usage was reminding me of – this construction – because it can’t really be cut down without losing something of its meaning, so it’s not quite a simple allusion padded out, but it seems like an oddly extended capsule summary, and then it hit me – this is a meme in text form. In, say, a Buzzfeed article, he would have written his description of the preceding circumstances and then added this guy:

– but here, he has to write out the blurb of the scene. It’s… once you make the mental translation, it feels fine, but until then it’s just… weird.

Many senior theses could be written about the potential of memes to form the basis of a new ideographic written language, Darmok-style.

like a real-life version of Frank the Tank, the beer-bong-hitting character played by Will Ferrell in Old School. (p. 105)

It seems like the prime use of the “real-life version” qualifier used here should be for when the character referenced is either themselves so removed from the realm of possibility, or the setting in which they appear is, that it’s necessary to clarify that the person you’re talking about actually exists.

That said, I can sort of see it as being used specifically when the character isn’t that unrealistic, but the main eyebrow raiser is how much unnecessary information is tacked on so clunkily. (Though, see below, there’s no explicit mention that Old School is a movie, so…) Compare to something like “a real-life version of Will Ferrell’s beer-bong-hitting Frank the Tank from Old School.” The “from Old School” bit still feels a little bit tacked on and superfluous if you know about Old School, but it flows a bit better going from the most relevant, central part of the reference (because let’s be honest, in Old School as in most comedies, the character is the comedian and v.v.) to the clarifying details and finally the larger context.

dressed as Emmett “Doc” Brown from the movie Back to the Future, in a white lab coat and a crazy snow-white wig. (p. 133)

This isn’t so much an unnecessary explanation as putting the punchline first. If he’d written “in a white lab coat and a crazy snow-white wig – he was dressed as Emmett “Doc” Brown from Back to the Future,” (I don’t think that you need to explain that Back to the Future is a movie) then not only would it capture things the same way he experienced seeing them, it’d set up a mini-payoff: He’s wearing a lab coat… white wig… is… holy fuck, is he dressed as Doc Brown!?.

reminds him of Logan’s Run, the dystopian sci-fi movie where people are killed when they reach the age of thirty, in order to prevent overpopulation. (p. 140)

If you’re familiar with Logan’s Run, then no gloss is necessary. If you’re not, then mentioning it gains nothing over, say, “makes him think of a dystopian future where people are killed when they reach the age of thirty”.

a different kind of person – young, male, amoral, perhaps not as evil as Patrick Bateman, the investment banker serial killer antihero of American Psycho, but cut from the same cloth. (p. 157)

Without stepping into the debate over anarthrous nominal premodifiers AKA false titles, I’ll just point out that, here

- “investment banker serial killer antihero” is at least two words too long to read smoothly,

- if you’re using Patrick Bateman as a reference, glossing him like this is – again – clunkeh liek woah, and

- in lieu of the glossing practice mentioned above, why not use one of the illustrative, character-defining scenes from the referenced work – get your in-joke allusion and deliver the meat of the reference, a la: “a different kind of person – young, male, amoral, the kind you can imagine going on about Huey Lewis and the News right before hacking someone to pieces with an axe.”

reminds me of Chauncey Gardiner, the simpleton hero played by Peter Sellers in Being There, who rises to become an advisor to the president of the United States, and at the end of the movie appears headed for the Oval Office himself. (p. 165)

Sure, I guess? I mean, Gardiner – and I’m going by Wikipedia for this – seems to be much more of an explicit Christ figure, and I would’ve gone with Forrest Gump for the “simpleton who falls ass backwards into awesomeness”, but regardless – apposition, AHOY!

sidling up to me one day, like Lumbergh, the smarmy boss in Office Space, (p. 214)

This adds to the overall feeling of dissonance. While recognizing that, yeah, it can get hella awkward to have to keep glossing a specific movie reference, it’s also re-e-eally unlikely that anyone who didn’t know about Office Space on page 60 would have gone and seen it by page 228 214.

It’s like that old movie, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, where all the different teams are trying to find the treasure. (p. 217)

Also okay with this one because (although I cut the context here) it takes place in spoken dialogue, and stuff like this – reduplication, elaboration, rephrasing – happens all the time in spoken English.

Drinking the Kool-Aid is a phrase everyone in Silicon Valley uses to describe the process by which ordinary people get sucked into an organization and converted into true believers. (p. 51)

This is a weird sort of doubly-removed allusion, or maybe just one that’s been carried a ways along a euphemistic treadmill. Initially referring, figuratively, to literal mass suicide a la Jonestown (n.b. the actual drink was either Kool-Aid, “Flavor Aid”, or a mix, either on a mixing-vat or a cup-to-cup basis), it softened to just the sort of slavish acceptance and blind belief in a cult-like idea structure that led to the suicide (‘course, a lot of those cult members who couldn’t or wouldn’t drink the Kool-Aid were straight-up murdered via injection, Aktion T4 style), and from then just to being a real true believer in a group.

The point is it’s not so much a process as a threshold or a turning point. Drinking the Kool-Aid is something you really only do if you’re already all-in, so you either will drink the Kool-Aid (once you cast your past doubts & life aside), you have drunk the Kool-Aid (and are now, ha-ha, a Level VIII Operating Thetan), but drinking the Kool-Aid really only makes sense to describe the precise moment of utter commitment, the point where your value system shifts.

Like, your buddy Joe joined Evil Corp, ’cause a paycheck’s a paycheck, and things were pretty cool, until you had a big Ultimate Frisbee tournament scheduled, and he was the core of your spread offense, but he let himself get kept late one Friday to finish up a vital but meaningless project (like, organizing a social media summit, or something) – that one evening, yeah, he was drinking the Kool-Aid. (I’d go so far as to say that ‘drinking the Kool-Aid’ would be the precise moment he made his decision.)

TL;DR – The drinking of Kool-Aid retains the all-or-nothing connotations of its suicide-pact origins, and is ill-suited to ongoing acclimatization.

DISC is based on concepts created in 1928 by a psychologist named William Marston, who also created the comic book character Wonder Woman. That tells you pretty much all you need to know about DISC. (p. 59)

Just a little bit lazy, here. I originally tried to read into this something about the dominance/submission themes that Marston explicitly included in Wonder Woman, female empowerment, bondage, his own nontraditional private life, until I realized that, no, the message so far as I can tell is “dude created a comic book character therefore let us now laugh at his academic work”.

They are like a real-life version of the comedy done by Ricky Gervais in the British version of The Office, where the goal is not so much to make you laugh as to make you feel uncomfortable. (p. 79)

Given the relative popularity to a US audience of the US The Office vs. the UK The Office, and the marked difference in tone between them, I’m okay with this. (Basically, if it had occurred in another context not peppered with real noodle-blinkers, I wouldn’t’ve said boo.)

blended the DNA of Tony Robbins with the DNA of Harold Hill, the aw-shucks shifty salesman from The Music Man. (p. 128)

Just mildly clunky is all. Duplicated “the DNA of” and another apposite of an allusion.

I feel like George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life – I was just about to jump when an angel appeared. (p. 178)

Yeah, so, I get the whole “saved him from suicide” joke/reference, but Clarence didn’t actually change anything in George’s life, whereas this guy is bringing news of a pretty big fuckin’ change, so…

It’s like the final scene from Invasion of the Body Snatchers, where you think Donald Sutherland is still human, but then he points and opens his mouth and you realize he’s become… one of them. (p. 196)

Here, though, this works. Why? I think because first, it’s written in a much more naturalistic, spoken style. You can imagine actually saying this, compared to – seriously, try it – “The scene feels like something out of Office Space, the Mike Judge movie about life as a corporate drone at a company called Initech.” You can type this shit, but you sure as hell can’t say it.

Second, there’s not the same level of internal dissonance regarding what the audience is expected to be aware of. This strikes the sweet spot where, if he’d gone on to add that the movie is about aliens that gradually take the places of people, becoming ‘pod’-people… yeah; and if he’d just said “the final scene from Invasion of the Body Snatchers“, even if you could guess which movie he meant, would you really remember it in sufficient detail? Probably not. The supporting detail here works because it serves to further refine just what is being referenced, rather than zooming out to provide an encyclopedic summary.

a scene from Donnie Brasco, where Al Pacino plays a gangster and Johnny Depp plays an undercover FBI agent who has infiltrated the mob. In the YouTube clip, Pacino confronts Depp about being a rat. He says he put his reputation on the line for Depp, and if Depp turns out to be a rat, Pacino is a dead man. (p. 199)

This is interesting because in most of the previous movie references – though not all – the character name is featured or, at least, the actor’s playing a character is made explicit (such as the Bill Murray Groundhog Day reference). Here, after the brief set-up to indicate their roles, it’s Pacino and Depp carrying the action.

And here could be a whole disquisition on the modern celebrity actor and the trends in personal branding that lead to such logical extremes as Jean-Claude Van Damme playing Jean-Claude Van Damme in a movie inspired by the real life of Jean-Claude Van Damme, or more commonly to our talking about, for example, Bill Murray or John Cusack or Nicholas Cage doing things in the movie, not their characters, to the point where it seems almost impossible for a character to ever fully encompass the actor so that when we talk about that time Bruce Willis shot Alan Rickman and threw him off a building, while we’re at some level aware of the fact that it was the character John McClane, played by Bruce Willis, and Hans Gruber as portrayed by Alan Rickman, our primary conception of it is still some sort of surreal dream where the real-life people we’re more familiar with than our next-door neighbors act out action-packed scenarios engineered to engross us and mesh with our own fantasies –

– but the main point is just that there seems to be no internal logic to when the character names are used versus, or in addition to, actors’. Here, I can see dropping it because of how many times the two are referred to in the short passage, but Stephen Root isn’t mentioned as playing Milton, nor Christian Bale Patrick Bateman; Donald Sutherland’s character in Invasion of the Body Snatchers goes unnamed, and does knowing that Will Ferrell’s character in Zoolander was named Mugatu really add anything to the effect of the quote?

Are we going to prick our fingers and burn drops of blood on a picture of Saint Peter, like in The Sopranos? (p. 200)

I mean, yeah, they did do this in The Sopranos, but… does this add anything? To know that he got this from a show? Maybe this is just me (after all, allusions are dependent on a specific cultural background, both in terms of inclusion and exclusion) but it’s like 99% clear to me just from the description of the ritual that this is an initiation rite, and maybe 80% sure it’s for the mafia.